The Winter Hill Air Disaster

February 27th, 2010. Today is the 52nd anniversary of the plane crash on Winter Hill, near Bolton in Lancashire in February 1958. 35 people were killed when the Bristol 170 Wayfarer in which they were travelling from the Isle of Man to Manchester's Ringway Airport hit the snow-covered summit in thick cloud. Of the 42 passengers and crew on board the aircraft only 7 survived. The disaster remains the UK's worst high ground air crash and since 1950 is the 11th worst overall for lives lost.

T HE PLANE had a crew of three (including one woman) and was carrying 39 men from the Isle of Man motor trade on a one-day trip to the Exide battery factory near Manchester. Its call sign was G-AICS, referred to as Charlie Sierra, and it was operated on the day, 27th February, by Manx Airlines, but was owned by and in the livery of Silver City Airlines.

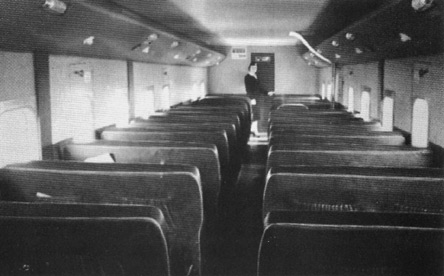

Bristol Wayfarer passenger cabin

The pilot and co-pilot (captain and first officer) were highly experienced airmen and took off from Ronaldsway Airport, a few miles southwest of Douglas, at around 9.15 am in what the pilot, Mike Cairnes (aged 38), is reported to have recalled as good weather. Thirty minutes later the aircraft was destroyed when it flew blind into the north edge of Winter Hill's summit at approximately 1,460 feet. Winter Hill is 1,498 feet high at the very top.

According to the subsequent public enquiry, the cause of the accident was the error of the first officer, William Howarth (aged 28), in tuning the plane's radio compass on the wrong beacon on the mainland, and to a lesser extent, the captain's failure to check it. What seems clear, however, is that those errors in themselves were not the only reason for the tragedy.

Why did the plane crash?

The Bristol Wayfarer was built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company in 1946, had been operated by Shell in Ecuador, and served on the Berlin airlift. BEA bought plane as freighter in 1950, then in 1952 it was acquired by Silver City Airways who leased it to Lancashire Aircraft Corporation at Blackpool in 1957 before it returned for operation by Manx Airlines at Ronaldsway. At some time in its life the freighter had been converted to carry passengers.

Silver City Bristol Wayfarer 170 Charlie Sierra G-AICS

Mr Cairnes had 6,000 hours flying experience of which 625 hours had been in a Bristol Wayfarer type of aircraft. Mr Howarth had served in the RAF from 1951 and flown Meteor jets, obtaining his commercial pilot's licence in 1954. He had 1,740 hours flying experience including 1,250 flying Wayfarers for Silver City, and had already flown with Mr Cairnes 3 times before the day of the Winter Hill disaster.

Charlie Sierra didn't crash because it was a poor aircraft or because it was flown by poor pilots. Neither did it crash because of any single mistake by one or both of its flying crew, like, for example, aiming it at the wrong beacon. Rather, the accident occurred through a sequence of events, none of which caused it directly but which put the plane in ever increasing danger until one final action drove it into the hill. This was not the finding of the public enquiry but is the conclusion a layman might reasonably draw on learning the principal facts.

Flying at 1,500 feet, the same height as Winter Hill

As they walked across the apron to Charlie Sierra at Ronaldsway Airport, Mr Cairnes (pilot) asked Mr Howarth (co-pilot) to book a flight plan at 3,500 feet, a perfectly safe 2,000 feet higher than Winter Hill. Ronaldsway control tower responded 'no' - it had to be 1,500 feet to the en route Wigan beacon on the mainland or a delay to take off, as another plane was due over the Isle of Man to Manchester at 3,500.

No-one wanted a delay, especially passengers on a day trip. So Mr Cairnes took off in the apparent belief that once the mainland was reached he'd be cleared up to his normal 3,500 feet. The forecast was cloud with periods of rain and a cloud base of 600-1,000 feet, but on previous flights along the same route he'd been sent up to at least 2,500 feet on entering the Manchester Control Zone over Blackpool.

On this occasion that did not happen. When Mr Cairnes contacted Preston Control at 9.38 he was offered a clearance to Wigan beacon at 1,500 feet, remaining in visual contact with the ground. He wasn't allowed to go any higher because another plane was travelling in the opposite direction at 2,500 feet and landing at Blackpool. Charlie Sierra was flying approximately east-southeast and its intended route from Blackpool to Wigan passed several miles south of Winter Hill.

Mr Cairnes could have refused the 1,500 feet clearance and circled over Blackpool until he was cleared for a higher altitude, but the plane was not yet flying in cloud and he knew that in any case there was no high ground on the route to Manchester over Wigan. So he reluctantly accepted the lower clearance he was offered and pressed on towards Ringway Airport, expecting to pass Wigan in a few minutes at 9.43. Oblivious to these goings-on, the day trippers from the Isle of Man were now about 25 minutes into their flight.

There's another factor that came into play during the flight and which contributed to fate of Charlie Sierra. The flying regulations required Zone Controllers to give the pilot a QNH (Regional Pressure Setting) in millibars to enable the aircraft's altimeter to be calibrated. 1 millibar equates to about 30 feet in altitude. On takeoff Mr Cairns was given the Holyhead QNH of 1024 millibars and would have set his altimeter accordingly. As he arrived at the English coast and entered the Preston Control Zone he should have been given the Barnsley QNH of 1021 millibars - a setting which would probably have put the plane some 90 feet higher, and 50 feet higher than the summit of Winter Hill. Due to confusion over the regulations, the pilot didn't receive it, and he also forgot to ask for it.

Flying in the wrong direction: Oldham, not Wigan

A short time after takeoff Mr Cairnes handed control of the plane to his co-pilot, Mr Howarth, and went down to the passenger cabin. In the captain's absence Mr Howarth tuned the aircraft's radio compass to one of the beacons in the Manchester Control Zone. For the chosen route, the correct beacon was Wigan. But he tuned it to Oldham, and no-one seems sure why, even after the public enquiry.

![]()

Tracks to Oldham & Wigan beacons from Morecambe Bay Light Vessel

It has been suggested that the co-pilot tried to do too many things at once while the captain was absent from the cockpit, or that somehow in his mind he equated Oldham with Wigan, or that he confused the two beacons' recognition signals MYL and MYK. For whatever reason, he tuned it wrong and Charlie Sierra was flying several degrees further north than it should have, towards the vicinity of Winter Hill.

When Mr Cairnes came back to the cockpit to retake the controls, Mr Howarth tapped the compass and gave a thumbs up. As the Wayfarer trundled along at 170 mph, over the coast near Blackpool then over Chorley, neither man noticed the error, nor did the flight controller at Manchester Airport. But on the ground, eyewitnesses watched the low flying plane pass into cloud in a direction that struck them as wrong. The pilots now lost visual contact with the ground as the cloud quickly thickened and it began to rain.

At 9.44, when Charlie Sierra should have been past Wigan several miles to the south of Winter Hill, it was flying blind over the valley near Belmont on the north side. But it wasn't on a collision course with the hill, even though its altitude was lower than the summit. Without further intervention the plane would have continued along the valley towards Oldham, the pilots would soon have resumed visual contact with the ground, then presumably realised their navigational error and altered course to be guided into Manchester Airport from the north.

A final step to disaster but not in the air

A few seconds before 9.45, Mr Cairnes turned the plane sharply to the right and steered it into the snow-covered peat a few yards away from the summit of Winter Hill, destroying the aircraft and killing 35 people.

Pilot turns right as advised, plane hits Winter Hill

He did this because he was told to. Half a minute before, Manchester Zone Control had asked him: "Have you checked Wigan yet, please?"

"Negative," he'd replied.

Manchester asked: "Are you in visual contact with the ground?"

"Negative."

The Zone Control officer speaking from Manchester was Mr Maurice Ladd. From its bearing on his cathode-ray direction finder and a faint echo he'd noticed at the edge of his radar screen, Mr Ladd could see that Charlie Sierra had gone too far to the east.

"Charlie Sierra will you make a right turn immediately on to a heading of two five zero. I have a faint paint on radar which indicates you're going over towards the hills."

"Two five zero right, Roger."

The plane collided with the ground 15 seconds later, having been able to complete less than 45 degrees of the turn.

Mr Ladd's intervention, causing the fatal turn, was examined during the public enquiry into the accident, in June 1958. The report states: "[Charlie Sierra] was well to the East of its course for Wigan Beacon, and it was dangeously near, on whatever course it was flying, to the white blobs on the radar screen which indicated high ground. Mr Ladd at once became anxious, especially because he knew that the aircraft was coming from the direction of Blackpool. It was on the basis of this anxiety that Mr Ladd at once, on seeing the first echo, sent out his instructions to CS to turn immediately to a course of 250°. Before the 10 seconds, which was required to deliver the message, had elapsed, a second echo came up on the screen, which confirmed Mr Ladd's anxiety by giving an indication of the direction in which the aircraft was heading. In fact, unfortunately, the aircraft, when the order was received, was rather further East and further North than Mr Ladd had reason to believe. His order to turn right was properly given on the basis of the information which he had and the judgement which he reasonably, and instantaneously, formed upon that information. His order was intended to take CS clear of the high ground. In fact, it brought CS into the side of Winter Hill. But Mr Ladd is in no way to be blamed. On the contary, he is to be commended for his prompt and energetic action in a moment of crisis in an endeavour, reasonable and well-judged though in fact unsuccessful, to save the aircraft from what was, in my view, a position of imminent peril."

Aviation historian Steve Morrin, in his book "The Devil Casts His Net" on the Winter Hill air disaster, concludes there was no single cause for the accident and that a fateful chain of events began even before takeoff on the Isle of Man when the flight was delayed 15 minutes in agreeing the clearance.

The ground slopes down to the left where the plane crashed into the hill, so it was the right wing that hit first, then the right undercarriage and engine, and as it cartwheeled over the snowy peat the aircraft broke up almost completely, with wreckage scattered over a wide area. Only the tail section remained relatively intact as it slewed to a halt about 250 yards from the first point of impact.

Wreckage at crash site, tail section mostly intact

Of the 42 people on board the flight, 35 men were now fatally injured or already dead. Mr Howarth, the co-pilot, was alive. He climbed out of the upside down remains of the cockpit into the snow and made his way up to the tail section where he attended to the flight stewardess, Jennifer Curtis, and from there up a little further to the road that leads from the summit to the transmitter station building.

Much of the top of Winter Hill is fairly flat in the form of a large plateau. The transmitter station is some 200 metres from where the tail section had come to rest. None of the handful of men working up there that morning were aware that a plane had just crashed close by (though one thought he'd heard a 'whooshing noise'). The aircraft had struck the other side of the summit from them, on the slope about 50 feet down. Mr Howarth swung open the entrance door of the building and said: "There's been a crash. Can you please help me?" So began the local response to the incident. The engineer in charge phoned the local Police Station in Horwich and handed over to Mr Howarth. A small party then set out to the scene of the crash with stretchers, re-tracing the co-pilot's footsteps in the snow.

The response to emergency

The crash occurred at 9.45 am and it was perhaps half an hour later when the transmission station engineers first arrived at the scene with their stretchers and busied themselves with taking some of the few survivors to the building for warmth and first aid. The first emergency services to reach the crash site were a policeman from Horwich Police Station, two ambulancemen, and a fireman, at around 11 am, having walked two miles across the snowy moor from where they'd left their vehicles, stuck in snowdrifts on the road that leads up Winter Hill. Two survivors were still lying amongst the wreckage and bodies of dead passengers. They'd been lying in the snow for over an hour and were now stretchered to the transmission station to join the others.

Stretchering injured passenger away from the wreckage

After the initial short silence, news of the disaster spread quickly and as morning became afternoon, the top of Winter Hill was teeming with people of all kinds: rescue parties, reporters, local doctors, policemen, ambulancemen, and as is to be expected, others who'd battled their way up through the mist with their dogs, to see what was going on.

Eventually, men from the local quarry together with a snow plough diverted from clearing the local highways cleared a passable route so ambulances could ferry the injured to Bolton Royal Infirmary and the dead to a temporary mortuary at Victoria Road Methodist Church in Horwich (there were 34 bodies; one of the initial survivors died in hospital).

At this point the police ceased to have any official responsibility for the crash site so they left it as it was, but they were forced to return in the middle of the night following news reports of souvenir hunters milling around the wreckage earlier in the evening. They remained on guard at Winter Hill until the Air Accident Investigation Branch of the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation had surveyed the scene and carted the wreckage away to a hangar at Liverpool Airport.

Meanwhile at the Methodist Church the bodies of those who died were prepared for identification and checked against the flight manifest. It wasn't completely accurate as a few of the original party had given their tickets others in the run-up to the flight. Over the next few days the deceased were taken to various local mortuaries for post mortem, then returned to the temporary mortuary keeper at the church, who arranged for them to be laid in coffins for transportation back to the Isle of Man.

Remembering the Winter Hill plane crash

The crash in 1958 is characterised as a 'forgotten tragedy' with only scant commemoration and remembrance. One of the survivors, Fred Kennish, returned to the Winter Hill area in 1989 as Mayor of Douglas. He was able to meet some of his rescuers, visit Bolton Royal Infirmary to say: "Thank you," and was received at Bolton Town Hall by the town's Mayor and Mayoress. He also unveiled a plaque on the outside wall of the transmission station. It was 1998 before a memorial to those killed in the biggest disaster to have affected the Isle of Man was unveiled in a private ceremony at Ronaldsway airport.

In January 2005, the pilot Mike Cairnes and air stewardess Jennifer Fleet (originally Curtis) revisited the site for the first time, the Rotary Club of Douglas laid a wreath, and the BBC in Manchester broadcast a short regional 'Inside Out' documentary about the tragedy. 50 years after the crash, in January 2008, a few articles appeared in Lancashire and Isle of Man newspapers and that February, Rotary Club members attended a memorial service on Winter Hill and laid a wreath. Another plaque was unveiled at the scene and a further one was unveiled in Horwich Heritage Centre. The crash is also commemorated by Horwich Rotary Club.

A DVD documentary was made in 2007 by Horwich Rotary Club and Horwich Heritage, featuring the memories of local people who helped in the aftermath of the crash. It was shown at a commemorative event on February 27th 2008, to mark 50 years since the Winter Hill disaster, and is available at Horwich Heritage Centre.

In many ways, in Britain, the 1950s are a bygone age. Air travel was still seen as inherently risky and it was a time of respect for authority and a stoical attitude to personal tragedy. There was none of the public outpouring of communal grief you see in the modern media, and the unfortunate bereaved were expected to suffer in silence and get on with things by themselves, with only their families for comfort. In addition, losing the breadwinner was usually a more severe economic blow to a widow than today, when more women are able to work for a living. There were no counselling services and probably very little travel insurance and sueing for compensation. The co-pilot Bill Howarth, who received most of the official blame for the accident, went on to a long flying career until he retired in 1990.

I was ten years old in 1958 and remember the accident taking place, but until recently I never bothered to find out exactly why or where in the moor it actually happened, even though I live on the slopes of Winter Hill and have cycled or walked there many hundreds of times. No-one discusses it much nowadays and the ramblers and joggers and mountain bikers and microlite flyers who pass by the spot where the plane hit the ground are oblivious to the history of where they are.

Looking west-northwest towards the Isle of Man from Winter Hill summit

Winter Hill is beautiful if not especially pretty and is visible from much of the Lancashire plain and beyond, standing in the distance with the mast at the top. From various places on its broad plateau you can swing your view through a wide and spectacular panorama from the Pennine wind farms to the north east, past the Manchester conurbation to the hills of Derbyshire and the telescope at Jodrell Bank, then south over Cheshire and the mountains of Wales in the far southwest with the Isle of Anglesea, Liverpool, then Blackpool Tower on the Fylde coast. The Lakeland Fells are often visible in the north west and Pendle Hill to the north. On a very clear day you can see the Isle of Man and in the south, the Wrekin, a hill near Telford in Shropshire.

Footnote: on 17th August 2010 I received the following email:

Dear Mr Taylor,

I have just read your eloquent and moving account of the true facts of the tragedy of Winter Hill. I became Mrs Michael Cairnes in March 1968, several years after the accident, but I learned all the details from my husband. This is the first account I have read that mirrors his remembrances exactly. My five wonderful step-children, and Michaels' and my own two children will be heartened to have the exact details so accurately portrayed. Michael is sadly no longer alive but his legacy of seven splendid children give me great comfort.

Thank you most sincerely for the incredible research and time taken to write the truth.

Respectfully,

Genevieve Pavlovic - formerly Genevieve Cairnes

Articles »